|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

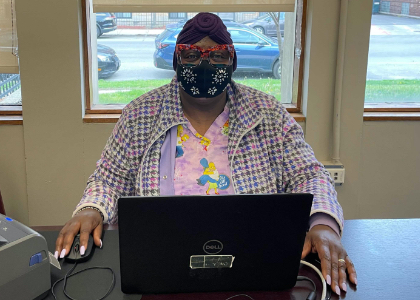

| Free pep talk with every COVID-19 test |

|

| |

|

| Carrol J. Banks, a testing coordinator for UChicago's COVID-19 testing program, gives what she calls "the speech" to many students. It starts when a student walks up to the check-in or the testing area, saying they're nervous for midterms or finals. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| "I gave [one woman] the speech. I told her, 'So you already know you passed, right?' She said, 'I did? How did you know?' And I said, 'Because I know you.' She said, 'How do you know me?' And I said, 'I'm looking at your face, sweetie. You're determined, you're going to succeed in life, and it's going to be okay.' The tears started […] and [during] finals week she came back and she said, 'I passed!'" |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Marshall Sahlins taught me how to think |

|

| |

|

|

|

| Sahlins in China in 1988. |

|

| |

|

| Anthropologist Marshall Sahlins, the Charles F. Grey Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus, died in April 2021 at age 90. In this excerpt from How to Think Like an Anthropologist (Princeton University Press, 2018), author Matthew Engelke, AB'94, explains what it was like to encounter Sahlins's work for the first time. |

|

| |

|

| I remember very well the first piece of anthropology I read. I was a first-year student at university, holed up in the library on a cold Chicago night. I remember it so well because it threw me. It challenged the way I thought about the world. You might say it induced a small culture shock. |

|

| |

|

| It was an essay titled "The Original Affluent Society" by Marshall Sahlins, one of the discipline's most significant figures. In this essay, Sahlins details the assumptions behind modern, Western understandings of economic rationality and behavior, as depicted, for example, in economics textbooks. In doing so, he exposes a prejudice toward and misunderstanding of hunter-gatherers: the small bands of people in the Kalahari Desert, the forests of the Congo, Australia, and elsewhere who lead a nomadic lifestyle, all with very few possessions and no elaborate material culture. These people hunt for wildlife, gather berries, and move on as necessary. |

|

| |

|

| As Sahlins shows, the textbook assumption is that these people must be miserable, hungry, and fighting each day just to survive. Just look at them: they wear loincloths at most; they have no settlements; they have almost no possessions. This assumption of lack follows on from a more basic one: that human beings always want more than they have. Limited means to meet unlimited desires. According to this way of thinking, it must be the case that hunters and gatherers can do no better; surely they live that way not out of choice but of necessity. In this Western view, the hunter-gatherer is "equipped with bourgeois impulses and paleolithic tools," so "we judge his situation hopeless in advance." |

|

| |

|

| Drawing on a number of anthropological studies, however, Sahlins demonstrated that "want" has very little to do with how hunter-gatherers approach life. In many of these groups in Australia and Africa, for example, adults had to work no more than three to five hours per day in order to meet their needs. What the anthropologists studying these societies realized is that the people could have worked more but did not want to. They did not have bourgeois impulses. They had different values than ours. "The world's most primitive people have few possessions," Sahlins concludes, "but they are not poor. … Poverty is a social status. As such it is the invention of civilization." |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| What does Hyde Park smell like? |

|

| |

|

|

|

| The candle version evokes "the nostalgic scent of Hyde Park's many bookstores and libraries, with notes of leather, patchouli, and musk." It's the most popular offering at Vicinity Candles, run by Annie Cantara, AB'17. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| If UChicago were a '90s video game |

|

| |

|

|

|

| UChicago campus, Gather Town version, built by historian Ada Palmer and a team of College students. |

|

| |

|

| Every year in her Italian Renaissance course, Ada Palmer, associate professor of history, has students reenact a papal election, with Rockefeller Chapel standing in for the Sistine Chapel. On Zoom, it wouldn't really work—so friends of Palmer's suggested she try Gather Town. |

|

| |

|

| "Zoom can't enable circulating through a space, ducking out for a private conversation, or walking to the middle of the room and suddenly making a big announcement, but Gather Town can handle those things," says Palmer. "As I looked into what it would take to make Rockefeller, I thought of how many other things—like receptions, dorm groups, RSOs, conference receptions, even a game like Humans v. Zombies—might be able to make use of it. So I thought: Why not make a whole campus?" |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| University chancellor Lawrence A. Kimpton greets Queen Elizabeth II during her visit to UChicago in 1959. |

|

| |

|

|

|

| The College Review, edited by Carrie Golus, AB'91, AM'93, is brought to you by Alumni Relations and Development and the College. Image credits: Anushka Harve, Class of 2024; courtesy the Sahlins family; courtesy Annie Cantara, AB'17; courtesy Ada Palmer; University of Chicago Library, Special Collections Research Center, apf1-05958. |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|